The idea of a government outlawing activities accomplishes only one thing clearly: It tells citizens that government has decided something is Wrong and now outlaws doing it. Sending A Message is the principle act behind the Swedish state’s promotion of its law against buying sex, and it is the principle act behind all the other politicians and would-be policymakers who want the law for their countries. Everyone wants to be seen to be Taking a Stand against immoral behaviour. Try bringing evidence into the conversation and you will quickly learn how irrelevant it is; you can find Swedish promoters themselves saying things like We know it doesn’t work but we want to be in the forefront of Gender Justice. This is about standing up for how you think society should be and doing it publicly, and trying to save people from their own immoral selves by outlawing bad things that attract them.

The idea of a government outlawing activities accomplishes only one thing clearly: It tells citizens that government has decided something is Wrong and now outlaws doing it. Sending A Message is the principle act behind the Swedish state’s promotion of its law against buying sex, and it is the principle act behind all the other politicians and would-be policymakers who want the law for their countries. Everyone wants to be seen to be Taking a Stand against immoral behaviour. Try bringing evidence into the conversation and you will quickly learn how irrelevant it is; you can find Swedish promoters themselves saying things like We know it doesn’t work but we want to be in the forefront of Gender Justice. This is about standing up for how you think society should be and doing it publicly, and trying to save people from their own immoral selves by outlawing bad things that attract them.

Any other claim about what prohibitionist laws achieve when they outlaw social activities like sex, drinking and drugs is not supported by evidence. That’s because, after the law is passed and the message is sent, individuals deal with prohibition deviously. That is, social pressure is strong to go along with the moral stand taken, but on the private level folks don’t intend or aren’t able to stop taking their own pleasures. So buyers and sellers of drugs, alcohol and sex become creative, some of them maintaining a disapproving stance in public at the same time.

The main claim made by prohibitionism is its deterrent effect, which holds that people will be put off breaking the law a) simply because it is illegal; b) because they are afraid of being put in prison; c) because they do not want to be publicly shamed and lose social status, whether they go to prison or not. In Foucauldian terms a punishment has to be threatened that can rob the crime of all attraction, so the potential perpetrator stops. Shaming is thus proposed by those who would prohibit buying sex (names and photos published on a website, for instance). Heart-rending pictures of victims are distributed to add to the shame at wanting to participate. When those don’t seem to work, or when perpetrators go ahead and pay fines when they are caught instead of resisting charges, prohibitionists propose the ante be upped to obligatory jail sentences.

I wrote about deterrence early on in Sex Workers and Violence Against Women: Utopic Visions or Battle of the Sexes? The theory of deterrence sounds as though it might work to put people off getting punished, but people are not very logical or sensible when it comes to their bodily pleasures – eating, smoking, drinking, drug-taking, sex. I hope someone is documenting the techniques being used as part of a criminology project somewhere – let me know if you are! [Other uses of deterrence are more complicated, see Deterrence in Criminal Justice.] I do wish Foucault were here to talk with me about this.

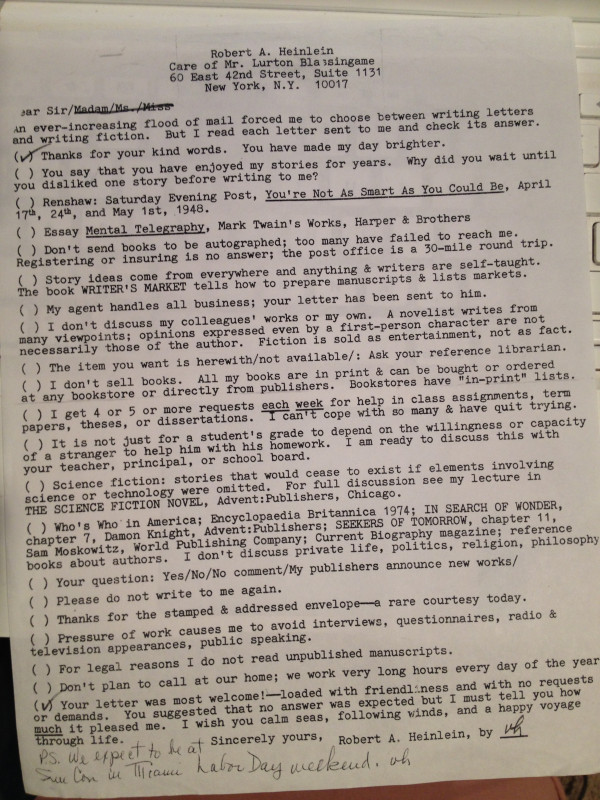

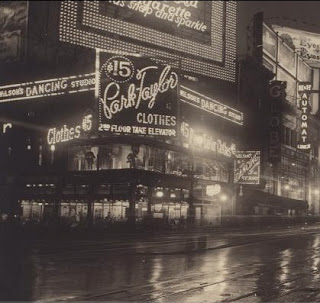

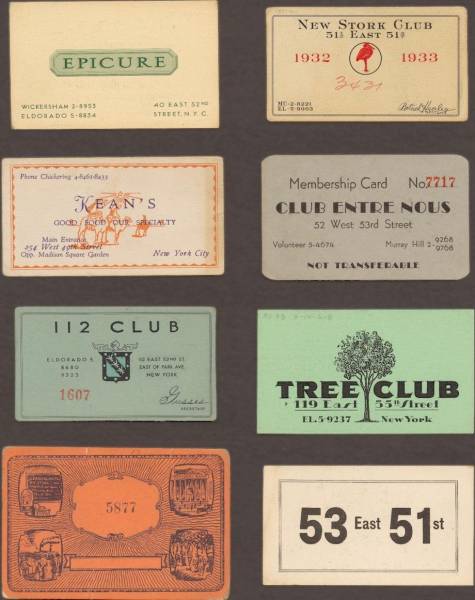

The prohibition of alcohol in the USA provides insights, though we shouldn’t generalise about everything and everywhere on the basis of them. I only bring it up because Slate just published these elegant cards patrons could carry and show at the door of drinking clubs in midtown New York between 1920 and 1933, the years when making and selling alcohol was prohibited. Calling it a club didn’t make drinking there legal, but if drinkers belonged to insider networks they would get a card, and doormen felt safer letting them inside the venues (the theory being that police and their informants wouldn’t manage to get a card).

The prohibition of alcohol in the USA provides insights, though we shouldn’t generalise about everything and everywhere on the basis of them. I only bring it up because Slate just published these elegant cards patrons could carry and show at the door of drinking clubs in midtown New York between 1920 and 1933, the years when making and selling alcohol was prohibited. Calling it a club didn’t make drinking there legal, but if drinkers belonged to insider networks they would get a card, and doormen felt safer letting them inside the venues (the theory being that police and their informants wouldn’t manage to get a card).

These cards represent clubs both famous and obscure. The card on the upper right would have admitted a partygoer to the glamorous Stork Club in its second home, which it moved into after it had been “raided out” of its first on West 58th Street. . . All of these cards are for establishments located on roughly the same latitude in midtown Manhattan. In the Prohibition years, according to Irving L. Allen, the blocks between 40th and 60th streets in Manhattan were rife with speakeasies.

The cards show how deviance develops when a market exists for an outlawed activity. Buyers and sellers find each other, including in upper social registers where patrons obviously must include some of the very people who have Taken a Stand and voted in a prohibitionist law. The cards also show how little deterred alcohol-drinkers were.

Then, of course, and far more convincing: all kinds of buying and selling sex are prohibited by criminal law all over the US, except in those few rural counties of Nevada where brothels are allowed. How in the world anyone could propose prohibiting the buying of sex as a deterrent is beyond me.

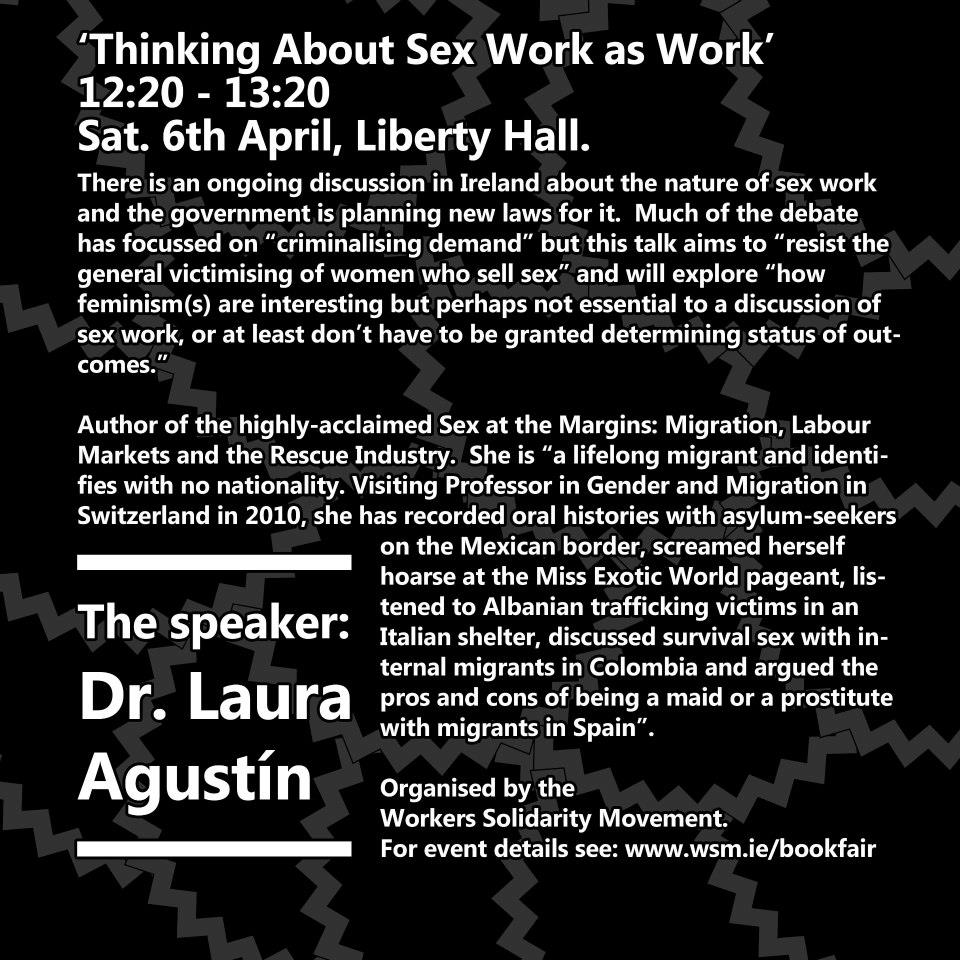

–Laura Agustín, the Naked Anthropologist